The OAuth 2.0 is a framework that allows third-party applications to obtain limited access to an HTTP service, either on behalf of a resource owner (basically a user) by orchestrating an approval interaction between the resource owner and the HTTP service (typically a content provider, such as a social network), or by allowing the third-party application to obtain access on its own behalf.

Objectives

In the following post, I’d like to explore the following:

The following content is based on several resources, among them are the official IETF documentation, the Wikipedia article, and OAuth 2 in Action, a book by Justin Richer and Antonio Sanso.

Brief History

The story of OAuth starts in November 2006 when Ma.gnolia was about to integrate its services with Appel‘s Dashboard Widgets. At the time, this kind of integration would normally be done by asking the user for their credentials on the remote system and sending the credentials to the API. The issue was, that Ma.gnolia used Twitter’s distributed identity technology – OpenID – to facilitate login. Which they don’t use credentials for authorizing and authenticating users. So Ma.gnolia looked for a solution to allow their members with OpenIDs to authorize Dashboard Widgets to access their services. A few developers from Twitter together with a developer from Ma.gnolia concluded that there were no open standards for such API access delegation.

In April 2007, this small group of developers created the OAuth discussion group, to write the draft proposal for an open protocol. In July 2007, the team drafted an initial specification. Eran Hammer joined the team and coordinated the OAuth contributions creating a more formal specification. At the beginning of December 2007, the OAuth core 1.0 final draft was released. Since then, it became a widely used open standard for access delegation.

Subscribe to get updates!

What is the OAuth Framework

As the brief history emphasise, the OAuth was created to address several issues and limitations pointed out with the authorization standards.

The client-server authentication

To understand these issues, let’s visit the traditional client-server authentication model by an example:

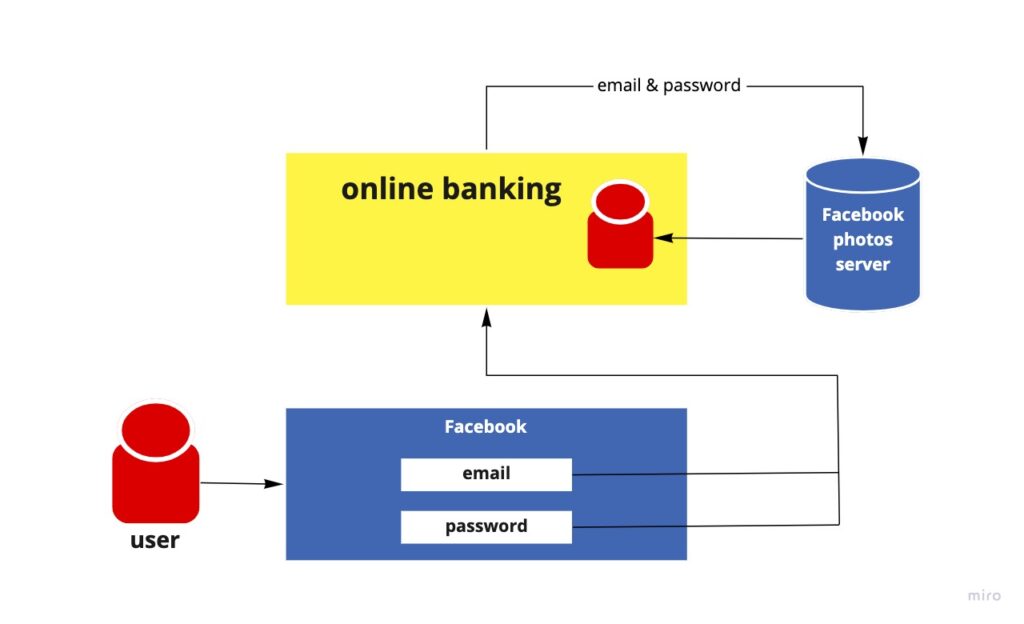

A bank developed a new online-banking website. The website designer thought that the UX can be improved by adding profile images. The developers said they don’t need to store the user image on their side. Instead, they can use users’ Facebook profile images. The access of the bank website to the Facebook profile image would work as follows:

The online-banking requests access restricted to the Facebook server by authenticating with the server using the user’s credentials.

The problems with client-server auth

Having the online-banking example in mind, to allow users to use their profile image, they would have to share their Facebook credentials with the bank. That means the bank will have to store the users’ Facebook credentials, typically, as clear text.

Despite the security weaknesses inherent in passwords, Facebook’s photos server is also required to support password authentication.

The bank website gains overly broad access to their users’ Facebook accounts, leaving the users without any ability to restrict duration or access scope to a limited subset of resources.

Once a user integrated their Facebook profile image, they cannot revoke bank access to their Facebook account without revoking access to all other third parties. And the only way to do so is by changing their password.

The authorization layer

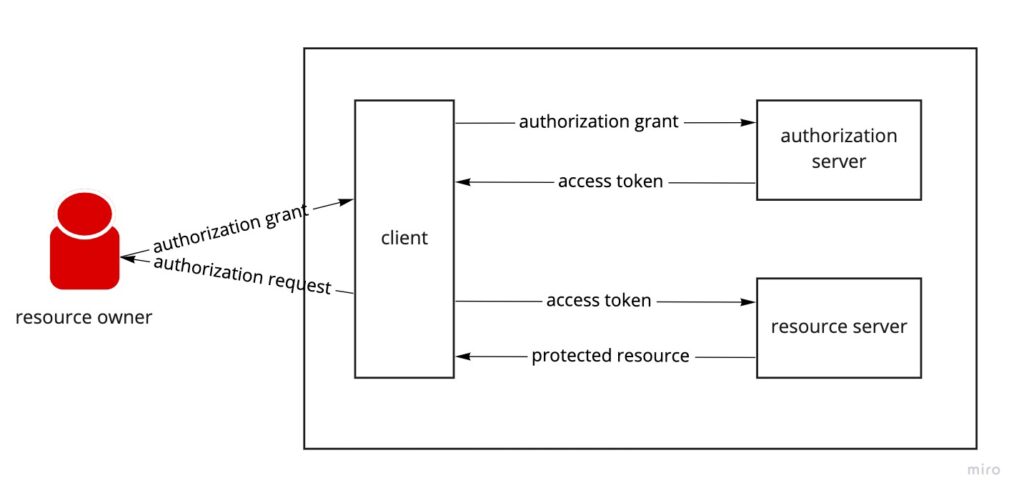

OAuth addresses these issues by introducing an authorization layer and separating the role of the client (the bank in our case) from that of the resource owner (the user). In OAuth, the client requests access to resources is controlled by the resource owner and hosted by the resource server. The OAuth is issuing a different set of credentials than those of the resource owner.

Unlike client-server authentication, which uses the user’s email and password to access the user’s resources. The OAuth uses tokens that are denoting a set of access attributes such as scope, expiry date, and more. These tokens are issued to third-party clients by an authorization server with the approval of the resource owner. The third-party client then uses the access token to access the protected resources hosted by the resource server.

Back to our example, the user of the online-banking can share their Facebook profile image with the online-banking without sharing their email and password. Moreover, the access token generated by the authorization server has a restricted scope to Facebook’s profile image. Meaning, the bank will have access exactly to what the resource owner gave them.

Common use cases of OAuth2

There are many different implementations of OAuth. Although the motivation behind the OAuth protocol creation, was for third-parties integrations, the use of it expanded to many other different areas.

In the Protests-Map application, we implemented “Sign-up with Google” provided by the Firebase Auth library. This service uses an OAuth token provided by Google identity.

Securing distributed systems with OAuth2

Most technology startups founded in the past decade are building and running their software systems in the cloud while implementing a flavour of a distributed system architecture.

One of the problems that come up with the rise of distributed systems, is API’s authorization. Back to our online-banking example, let’s say the bank has the following services on their system:

- accounts

- transactions

- credits

- savings

Each of the services runs as an isolated deployable unit, with its own database and mid-level API server. Now, let’s say some other services are only accessible for specific kinds of users, such as businesses accounts, or premium customers. How should we make sure that resources are protected?

Here is where OAuth come to the frame.

High-level description of the OAuth 2.0 mechanism

OAuth is a complex security protocol composing an accurate flow between four different roles and several components and steps to send information to each other. The two major steps of OAuth transactions are: issuing and using/validating tokens. Besides issuing and validating tokens there are other two steps, redirecting to URIs and refreshing tokens. Following are the main components involved in the OAuth 2.0 flow.

The OAuth 2.0 roles

- resource owner An entity granting access to the protected resources.

When it’s a person, it is referred to as an end-user. - resource server The server hosting the protected resources,

capable of accepting and responding to protected resource requests using access tokens. - client An application making protected resource requests,

on behalf of the resource owner and with its authorization. - authorization server The server issuing access tokens to the client,

after successfuly authenticating the resource owner and obtaining authorization.

The term client does not imply any particular implementation characteristics. Every application that requests a protected resource is a client.

An authorization server can be implemented as part of the resource server, or as a self-contained service. A single authorization server may issue access tokens accepted by multiple resource servers.

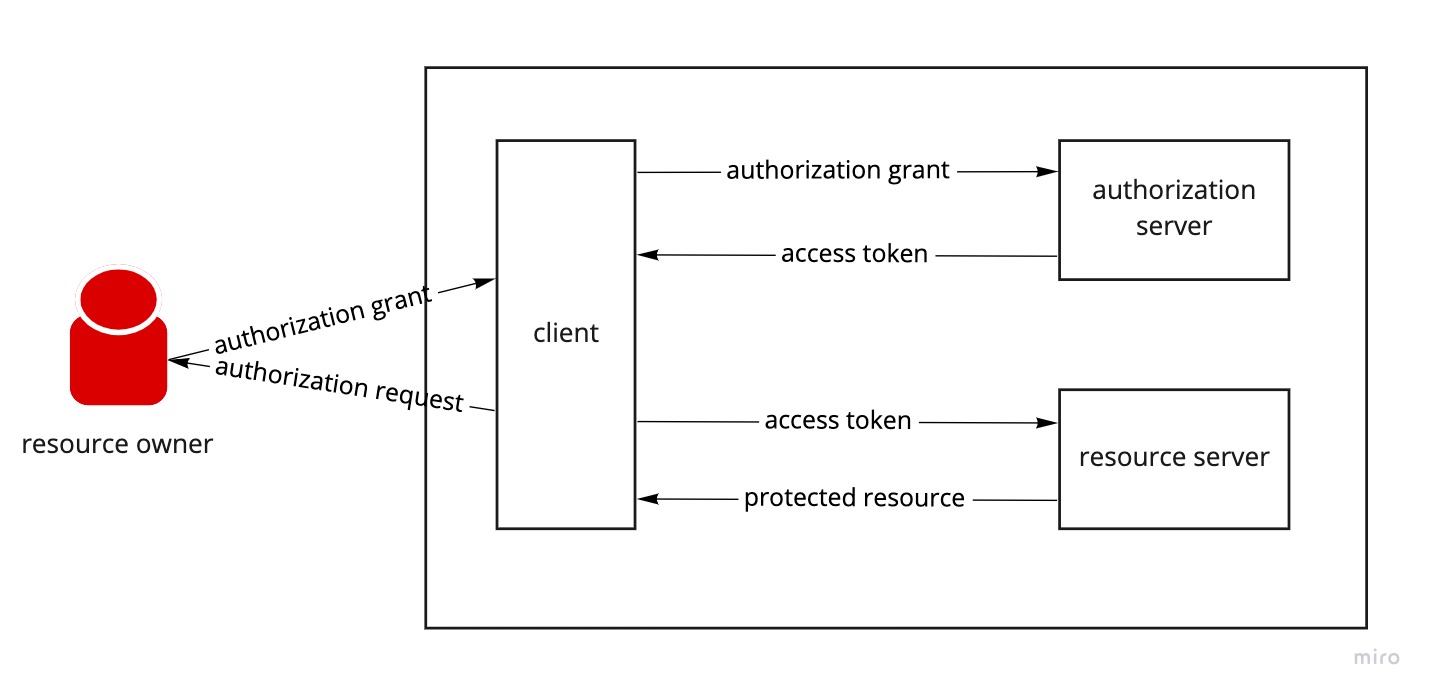

The protocol flow

- First, the client requests authorization from the resource owner.This request can be made directly to the resource owner, or preferably via the authorization server as an intermediary.

- The client receives an authorization grant.Which is a credential representing the resource owner’s authorization, using one of the grant types.

- The client requests an access token.By authenticating with authorization sever and presenting the authorization grant.

- The authorization server authenticates the client and validates the authorization grant.If valid, issues an access token.

- The client requests the protected resource from the resource server.And authenticates by presenting the access token.

- The resource server validates the access token.And if valid serves the request.

Starting with the resource owner, the process of the OAuth require the client app for an authorization grant code. This code uses a temporary credential to represent the resource owner’s delegation to the client. For instance, the user of the online-banking app wants to use their Facebook profile image. They tell the online-banking client app to use their image. The Facebook profile images server uses an API that the online-banking app knows how to process as well as that it needs to use OAuth to do so.

When the access token is expired, the client is notified that it needs a new OAuth access token, it sends the resource owner to the authorization server with a request that indicates that the client is asking to be delegated some piece of authority on the behalf of that resource owner.

The client is identified by an ID and requests specific items such as scopes through query parameters in the URL. The Authorization server can parse the parameters and act accordingly.

Next, the authorization server asks the user to authenticate (if they aren’t yet authenticated). The authentication is never seen by the client application.

Once the user is authenticated, they authorize the client app and the authorization server redirects the user back to the client app with the authorization code (there are different kinds of grant types, for the sake of simplicity, we assume using authorization code as grant type). The authorization code is included in a query parameter. The value of the authorization code is a one-time-use credential, and it represents the result of the user’s authorization decision.

As the client gets the authorization code, it sends it back to the authorization server with a POST request to the token endpoint.

If the request is valid, the authorization server issues an access token and returns it as a response to the client app.

Now the client app can send the request to the protected resource server.

The OAuth’s componets

Additionally to the roles we’ve seen earlier, the OAuth framework depends on several other mechanisms as follows:

- access token

- refresh token

- scopes

- authorization grant

Access Token

The token is issued by the authorization server, and it is passed through by the client to the protected resources which should validate it. The client should not care for the token content, its job is to carry the token from the authorization server to the protected resources. The client is completely oblivious to the token itself.

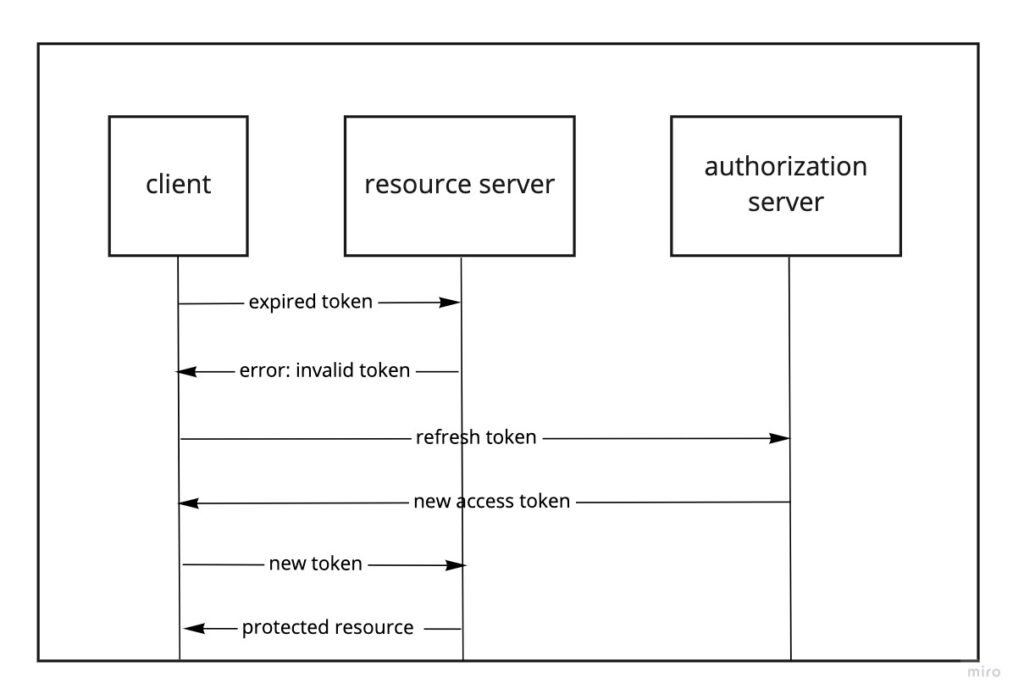

Access tokens have a short lifetime, typically something between minutes and hours. An access token can expand its lifetime by a refresh token.

Refresh Token

Similar to the access token, the refresh token is issued by the authorization server, but it’s not validated by the protected resources. The validation of an access token is done by the authorization server before it issues a new access token. The idea is that when an access token is expired and rejected by the protected resource, the client can ask for a new access token without interrupting the resource owner.

Scope

OAuth scope represents a set of access rights at a protected resource. Scopes are represented by strings and they cannot contain space values. By choosing the scopes, the resource owner can restrict the client to access specific resources and block the client from other resources.

Authorization Grant

An authorization grant is a credential representing the resource owner’s authorization (to access its protected resources) used by the client to obtain an access token. The OAuth specification defines four grant types: authorization code, implicit, resource owner password credentials, and client credentials – as well as an extensibility mechanism for defining additional types.